Leveraging the role of the justice sector to help tackle global health inequities, this year EWMI has begun new programs in South and Southeast Asia to compliment and strengthen ongoing global initiatives to end some of the world's most intractable diseases. The many barriers to effective vaccination programs include unlawful discrimination against some minority communities, which makes the last mile of polio eradication a struggle. A second barrier to combating disease is the resistance to treatments created by counterfeit drugs, a threat to one of the best hopes of reducing the malaria burden. Drawing on its years of experience with the justice sector in South and Southeast Asia, EWMI is targeting these risks to global health equity through two new programs in India and Cambodia.

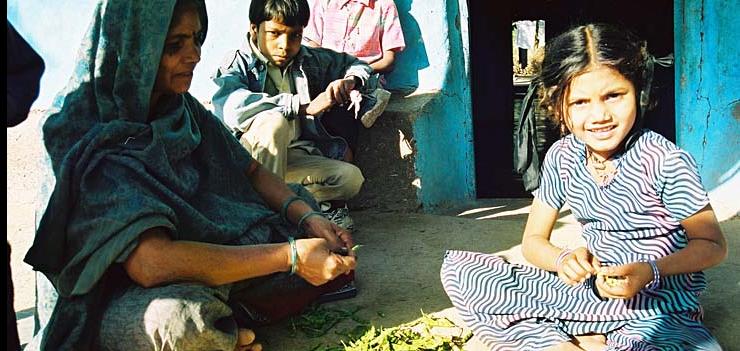

In India, EWMI has launched a pilot program with its local partner in Gujarat, the Navsarjan Trust, to monitor the unlawful discrimination that blocks polio vaccinations in marginalized communities. India’s Dalits (so-called untouchables) make up twenty percent of the national population, some 200 million individuals living at the margins of society. Despite the abolition of caste discrimination in the Indian Constitution in 1950, Dalits are regularly excluded from public life – including unlawful discrimination at health centers, where exclusion occurs at a rate of 10% according to a recent comprehensive study of untouchability practices. With more than 50 million Dalit children living in India, a 10% exclusion rate from access to health services translates into 5 million children missed: a grave risk to the goal of polio eradication. Unfortunately, accounts from villagers provide evidence that the systematic discrimination faced by Dalits also extends to polio vaccination campaigns.

The pilot monitoring program will map and address this problem through a series of interviews with 1000 families to determine the extent of the problem of missed Dalit children. Because the unlawful practice of health center discrimination is part of an array of illegal assaults on Dalits, EWMI works with the Dalit legal community – including the state-wide network of Gujarati “barefoot lawyers” – to independently monitor the scope of the discrimination. These advocates are well-versed in legal protections and have a presence in 3000 villages across the state, allowing unique access to Dalit neighborhoods and thorough coverage of a cross-section of districts. The pilot program will be complete in Fall 2011, and the results will guide a broader Dalit polio vaccination monitoring program to be completed in 2012.

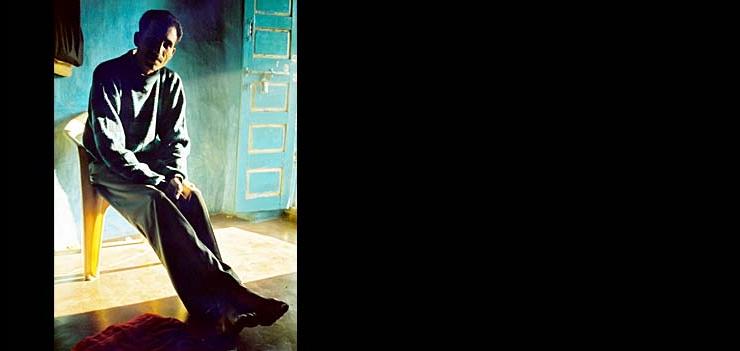

On the Thai-Cambodian border, the parasites that carry malaria demonstrate a dangerous resistance to the most effective anti-malarial drug, artemisinin. Counterfeit artemisinin combined therapies (ACTs) are to blame, and the illegal pharmacies that sell these fake drugs not only take thousands of lives in Southeast Asia, but threaten anti-malaria efforts throughout Asia by breeding new ACT-resistant mosquito-borne parasites.

EWMI hopes to control artemisinin resistance through justice sector interventions to stop counterfeit drugs. Under its USAID-funded Program on Rights and Justice, EWMI, working with the Cambodian Ministry of Justice, has launched research and training efforts with the nation’s judges and prosecutors to strengthen prosecution of the purveyors of counterfeit ACTs. Without effective prosecutions, police efforts to shut down illegal pharmacies can only go so far – convictions are necessary to stop the push-down pop-up effect that sees offenders continuing their trade across town. EWMI began its artemisinin resistance control work this year at the epicenter of the problem: launching its research and training program through work with magistrates from the key border provinces of Pailin, Battambang, and Bantey Meanchey.